The Forgotten Prelude to the Conquest of the New World

A History of the Conquest of the Canary Islands

In a land far from Spain, the chief of a tribal kingdom stands atop a volcanic ridge, watching as white sails creep ever closer.

Arriving in this alien world are the conquistadors — men driven by ambition, cloaked in steel, and carrying the banner of Christ. Their goal: to claim new territory for Spain under the guise of salvation.

It’s a scene that would play out again and again in the New World. But before the Americas were claimed in the name of empire and God, Spain waged a quieter, bloodier rehearsal — in the volcanic shadows of the Canary Islands.

The Fortunate Isles

For centuries, what lay beyond the Pillars of Hercules was a mystery — a realm wrapped in fear, fascination, and the promise of paradise.

To the ancient Greeks, the islands to the west were known as the “Fortunate Isles”, a blessed place where heroes might rest after death, untouched by time. Some believed these isles included the fabled Garden of the Hesperides, where golden apples grew and immortality was within reach.

The myth lived on into the medieval world. In the 6th century, an Irish monk named St. Brendan claimed to have glimpsed a miraculous island — one that appeared and disappeared in the mist — a place so divine it reflected heaven on earth.

This phantom island, known as San Borondón, was said to lie just beyond the Canary Islands. Even today, sailors speak of fleeting visions on the horizon, where myth and sea spray still mingle in the fading light.

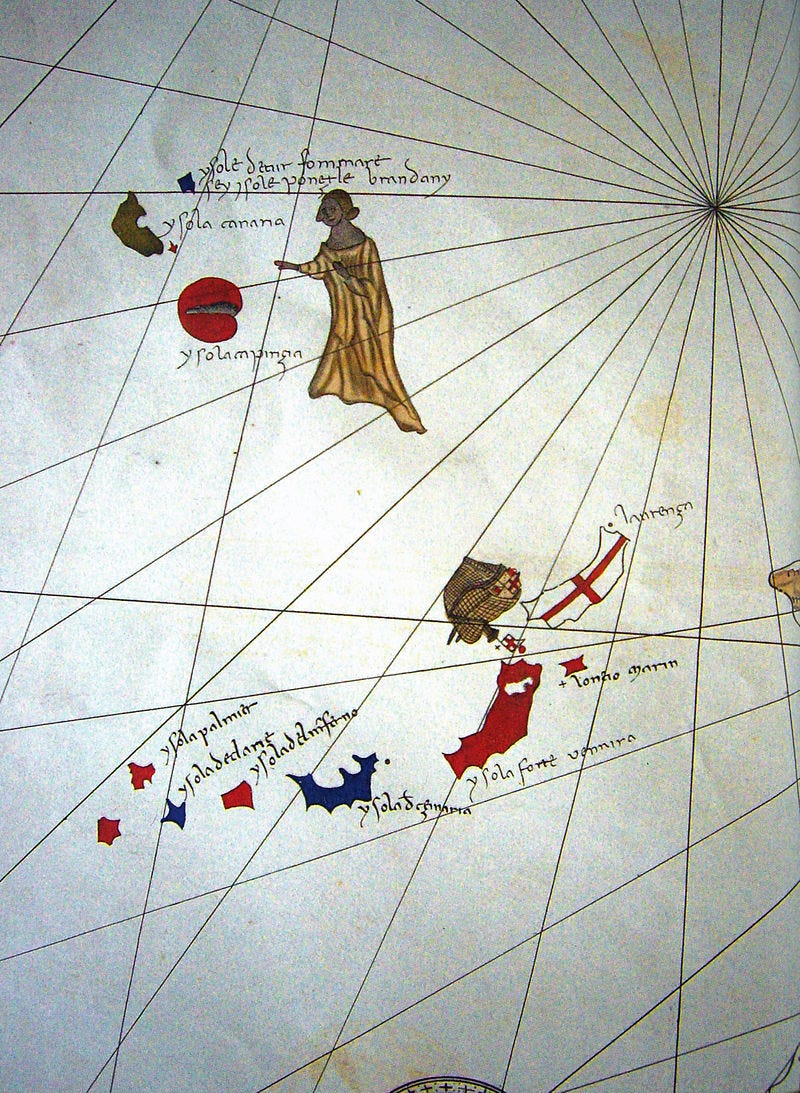

Maps and Myths

Though no ancient empire ever settled the Canary Islands, they were not unknown to the classical world. The archipelago appears on Roman maps as early as the 1st century CE, and long before that, it’s likely that Carthaginian explorers pushed into the Atlantic and caught sight of these distant shores.

The most detailed early report comes from Pliny the Elder, who wrote of an expedition dispatched by King Juba II of Mauretania. His scouts returned with tales of wild terrain, strange creatures — and an abundance of dogs. One island was named Canaria, after these animals. Another, Nivaria, meaning “snowy,” likely referred to present-day Tenerife, with its towering, snow-capped volcano, Mount Teide.

While Pliny claimed the islands were home to “only dogs and ruins”, we now know this was far from true. The Canaries were already inhabited by the Guanche people, a unique and isolated civilization whose origins stretched back centuries.

Though no Roman colony was ever founded, fragments of amphorae and ancient shipwrecks suggest that occasional contact — whether by storm or design — did occur. To ancient sailors, these islands were a whispered mystery: distant, wild, and half-real, perched at the edge of the world.

The Guanche

For over two thousand years before European sails appeared on the horizon, the Guanche people lived in complete isolation on the Canary Islands. When the Spanish arrived, they found no boats, no writing, and a way of life that resembled the Neolithic age.

This was a mystery in itself — the ancestors of the Guanches must have crossed open ocean to reach the islands, and yet, by the time of contact, even fishing boats had vanished from their society. Some early European chroniclers speculated they were descendants of Roman prisoners marooned on the islands. But archaeological evidence and recent DNA studies tell a different story: the Guanches predated Rome, and their genetic roots lie in the Berber peoples of North Africa.

Despite lacking boats, the Guanches were capable deep-sea divers. Skeletal remains show signs of exostosis — ear bone growth from repeated exposure to cold water — revealing a culture adept at harvesting the ocean by swimming, not sailing.

They lived in caves and stone villages, cultivated barley and wheat, and herded goats and sheep. Their society was organized and spiritual. Each major island was divided into tribal kingdoms — menceyatos on Tenerife, guanartematos on Gran Canaria — ruled by menceys or guanartemes who held both political and sacred authority.

Isolated for centuries, their culture evolved in unique ways. On La Gomera, they developed a whistling language, Silbo Gomero, to communicate across deep ravines — a practice still preserved today.

Most striking of all were their mummification rituals. The dead, wrapped in animal skins, were carefully preserved in mountain caves. These “xaxo” mummies, when discovered by the Spanish, provoked awe and confusion — the conquerors compared them to Egyptian embalming, and yet the practice was wholly indigenous. Today, many of these mummies can still be seen in the Museo Arqueológico in Tenerife.

Their mythology was deeply tied to the land. On Tenerife, Mount Teide loomed as a sacred and fearsome place. The Guanches believed a powerful being — often described as a great black dog — guarded the volcano and punished those who dared to climb it at night. The Spanish likened this creature to the Devil, but for the Guanches, it was part of a spiritual landscape woven into daily life.

A society without iron, without wheels, without ships — but not without meaning, identity, or power. And soon, they would be forced to defend their world against one that seemed to come from another age.

A Second Discovery, A First Obsession

With new maritime technologies emerging in the 12th and 13th centuries — from the lateen sail to the magnetic compass — Europe’s gaze turned once more to the open Atlantic.

In the early 1300s, the Genoese navigator Lanzarotto Malocello reached the northernmost island of the archipelago — today called Lanzarote in his honor. His voyage reintroduced the Canary Islands to Europe, no longer as mythical “Fortunate Isles,” but as real land ripe for exploration, trade, and exploitation.

In the decades that followed, expeditions arrived from Majorca, Portugal, and Castile, each probing the islands' coastlines and resources. In 1341, a Portuguese-sponsored mission led by two Florentine captains — Angiolino del Tegghia de Corbizzi and Nicoloso da Recco — sailed through the archipelago. They mapped the islands, collected orchil (a valuable purple dye from lichen), and goat hides — and captured several islanders to sell as slaves.

These early contacts were fleeting and opportunistic. No permanent settlement was made in the 14th century. But the allure of the islands — their strategic location, resources, and potential for Christianization — had planted seeds of imperial ambition.

In 1344, the King of Castile secured a papal bull granting him lordship over the “Fortunate Isles,” claiming spiritual authority as the justification for territorial expansion. Yet Portugal, with its own Atlantic ambitions, contested the claim. For over a century, both kingdoms eyed the islands, launching rival expeditions and diplomatic maneuvers.

The rivalry was finally resolved by the Treaty of Alcaçovas in 1479, which marked one of the earliest formal divisions of the non-European world: Castile was granted the Canaries, while Portugal gained control of Madeira, the Azores, and West Africa.

It was a quiet precursor to the Treaty of Tordesillas two decades later — and the first sign that the European powers were already carving up the world before the New World had even been discovered.

Conquest

The conquest of the Canary Islands began in 1402, when Jean de Béthencourt, a Norman nobleman in service to the Crown of Castile, landed on Lanzarote. Though French by birth, Béthencourt had Castilian backing — an early example of how ambition, patronage, and faith would drive European expansion.

From this initial foothold, the Spanish set out to conquer the archipelago island by island, over the course of nearly a century. Some fell quickly, others fought bitterly. But with each campaign, a familiar pattern emerged — one that would echo across oceans in the decades to come.

Here, in the Canaries, we witness the birth of Spanish colonialism.

As they would in the Americas, the Spanish brought with them steel, horses, and smallpox — weapons as devastating psychologically as they were physically. Against wooden spears and stone axes, Spanish swords cut through with ease. Horses, never before seen by the Guanches, became beasts of terror. Disease, invisible and unstoppable, softened resistance before swords could even be drawn.

But conquest wasn’t only about brute force. Just as they would later do in Mexico and Peru, the Spaniards played a game of strategy, trickery, and manipulation — and often turned on each other in the process.

Infighting among the invaders was common. Power struggles and personal ambition led to feuds, betrayals, and broken alliances, much like the rivalries that would later pit Cortés against Velázquez, or Pizarro against Almagro. The conquest of the Canaries was not a united mission, but a series of chaotic, often disjointed campaigns — driven as much by greed as by royal mandate.

Tactics tested here would become standard practice in the New World. On La Palma, the Guanche leader Tanausú was lured into peace talks — only to be ambushed, captured, and paraded as a trophy of conquest. A generation later, Atahualpa, the Inca emperor, would fall victim to the same ploy.

The bloodiest chapter of the conquest was written on Tenerife, the final island to resist. Here, the indigenous menceys refused to yield. In 1494, the Guanches achieved a stunning victory at the First Battle of Acentejo, ambushing Spanish forces in a narrow gorge and inflicting a humiliating defeat. The site is still remembered today as “La Matanza” — The Slaughter.

But the victory was short-lived. The Spanish commander Alonso de Lugo, seasoned and ruthless, returned the following year with reinforcements, new strategies, and a renewed sense of vengeance.

In 1496, Tenerife fell. The mencey Bencomo was killed, many warriors were slaughtered, and the survivors were either enslaved, assimilated, or killed by disease. By 1500, the Canary Islands were fully under Castilian control.

The conquest of the Canaries was not just a regional war — it was a prologue. The tactics refined here would be carried across the Atlantic. The Guanches, like the Taínos, the Mexica, and the Inca to come, faced an enemy from another world — one armed not just with superior weapons, but with a blueprint for domination.

Steel and Silence

Long before Spanish banners were raised over Tenochtitlan or Cuzco, they flew over the jagged ridges of Tenerife. Before the ships of conquest sailed into the Caribbean, they anchored off the black volcanic sands of the Canary Islands.

The tactics, the ideology, the machinery of empire — all were rehearsed here. Divide and conquer, forced conversion, strategic betrayal, the weaponization of fear — and of faith. The Guanches were the first to face them. They would not be the last.

Yet the story of the Canaries is often told in passing, a historical footnote to the “real” conquests that followed. But to ignore this chapter is to misunderstand the origins of European colonialism.

The Canary Islands were not merely stepping stones on the way to the New World — they were the blueprint. The Guanches were not a forgotten people — they were the first people to stand against what would become a global tide.

In their resistance, we glimpse echoes of what would come. And in their fall, we find the opening act of an empire that would reshape the world.

https://linktr.ee/jacoboconnormarvin