How California Became an Island (on the Map, at Least)

The story of a strange cartographic mistake that lasted centuries

Located on the western edge of Mexico, the Baja California Peninsula stretches for 775 miles of varied landscapes; from semi-arid desert regions to woodlands and even salt flats. The peninsula was formed 12 to 15 million years ago as tectonic plates shifted, causing a rift that is the gulf of California. But while the geography of the peninsula is well understood today, it wasn’t always that way.

For hundreds of years, many believed that California was an island. This strange error was not just a simple mistake but reflected the stories and beliefs of early Spanish travellers who visited the region.

Perhaps even more curiously, California had not always been displayed as an island on the map. The earliest maps of the region are, in fact, more accurate than the ones that came about in the 17th century. Who were these early explorers to map this area and how did the idea of what California looked like manage to change so drastically?

Hernan Cortes, who is of course famous for his conquest of the Aztec Empire, also lends his name to another way of referring to the Gulf of Mexico, the Sea of Cortes. After the monumental success of Cortes over the Aztec empire, Cortes’ power and influence began to grow and he looked to expand the territory he now controlled. The Spanish crown had been happy enough to leave these conquistadors relatively unchecked while they were discovering new lands and bringing back treasure ships filled with gold to Seville, but the crown was getting nervous, especially when it came to Cortes who had begun his conquest whilst going against the orders of a superior. It was against this backdrop that Cortes now set his sights upon exploring the North-West of Mexico and the currently unknown lands of Baja California.

But Cortes wasn’t the only one looking for new territories in the lands surrounding the now fallen Aztec Empire. The story of his success had brought competition, and to make things worse for him, by 1527, the Spanish Crown had sent Nuno Beltran de Guzman to balance out the power of Cortes. Cortes and his allies had been enjoying free reigns over the lands he had conquered, but Guzman’s arrival put an end to that. By 1528, Guzman was installed as the head of the first Audencia, an official colonial government for Mexico.

Guzman had been installed the limit the power of Cortes, but he was equally as power hungry. He stripped land from Cortes’ allies and Cortes was forced back to Spain to defend himself. This left the exploration open for Guzman who made his way north where he had heard rumours of a city of gold known as Cilbola. Rumours of cities of gold took many forms for the conquistadors, Cibola was rumoured to be not just one city but several, made of gold lying to the north of the Aztec empire. Guzman was not just looking for Cibola though, he also heard rumours that a race of warrior women, the Amazons, lay to the north of the Aztec empire too.

Members of Guzman’s expedition noted that Guzman himself was especially susceptible to these kinds of rumours. But where had these ideas come from? Of course, stories of the Amazon’s had been around since the time of the ancient Greeks but they managed to take on a new interpretation as the age of exploration began.

Columbus himself spoke of an island called Matinino, likely Martinique, that was inhabited by only women, where men were only allowed to come to the island for reproduction. He expressed a desire to find these women, as well as any other strange beings that might be found in this “New World.”

But he came up empty handed, he wrote back to the Spanish monarchs that he had “so far found no human monstrosities, as many expected.” What? Why would people be expecting to find human monstrosities on the other side of the earth.

Well for almost as long as homo-sapians have existed we have been dreaming up human monstrosities. Just take the Lion-head man from Germany as an example, some of the earliest human artwork, dating back between 35 – 41 thousand years ago.

As humans advanced and began writing they continued to blend fiction with reality, the histories by Herodotus was not intended as a fictitious work but contained accounts of winged serpents in Arabia and gold digging ants in India.

And history books continued to be a blend of fact and fiction, especially in the middle ages. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain is remarkably accurate when compared against archaeologically demonstratable facts but it also gives us the stories of King Arthur pulling a sword from a stone, fighting dragons and hanging around with an old wizard called Merlin.

An especially influential text from the medieval period that influenced the conquistadores would have been Mandeville’s Travels. The book reports to be a travel memoir written sometime between 1357 and 1371. The memoirs are written by an Englishman named John Mandeville who likely never existed but drew inspiration from other travelogues at the time and adding his own embellishments. The Travels of Marco Polo had been published less than a hundred years earlier and so much inspiration was drawn on from here.

Marco Polo we can almost safely say, did make the journey to Asia he claimed to. While there are elements that certainly could have been embellished, many of the fantastical elements come from a lack of ability to comprehend certain animals at the time. Marco Polo’s description of a horned, four-legged creature could only be interpreted by many as to be a unicorn.

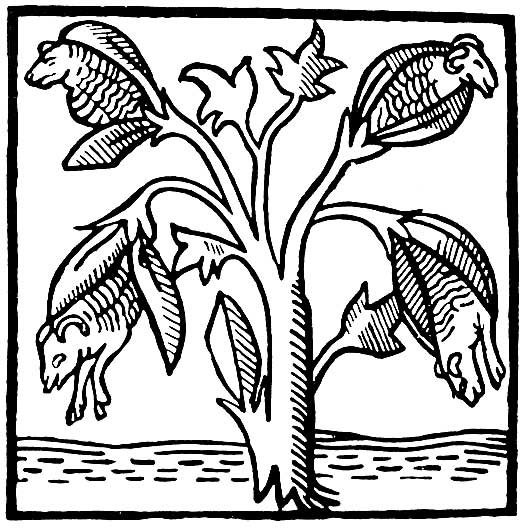

Whoever the author of Mandeville’s Travels was seemed to fall into the same similar kind of trap of not quite fully comprehending things outside of Europe. People had been travelling along the silk road for centuries but few, if any travellers other than Marco Polo or Ibn Battuta, travelled the routes extensively. And so, when commodities would arrive, there was only rumours about where they had come from, and people’s imaginations could run wild. In the case of Mandeville’s Travels, he claims to have seen where cotton has come from. A plant, with small sheep growing from it from which the cotton wool is harvested.

His most curious oddities though are the humanoid beasts that he claims to have encountered. Many of these creatures he has heard about from other travel authors compiling them all into his travelogue. The monopod’s of India that use their feet to shield themselves from the son, claimed to have been seen by Isadore of Seville around 600AD. Mandeville talks about the headless beings, the Blemmyae, and the dog-headed humans that the Greeks had claimed to have seen as well. And of course, there were the Amazons, perhaps alongside fictitious cities of gold such as Cibola and El Dorado as the most widely believed in myths of the time by the early Conquistadors.

The early explorers would have been reading books such as Mandeville’s and expected the world to be full of these “human monstrosities” as Columbus put it. Many claimed to have seen the Amazons. One early explorer claims to have seen “a tower on a tip of the land that is said to be inhabited by women who live without men.” A Spanish Conquistador, Francisco de Orellana, named an entire river after them. On his expedition travelling the length of the Amazon, he encountered a number of groups of warrior women that fought in the manner of the Amazons alongside men.

While these myths became less prevalent as more people came and saw the “New World” for themselves, the idea of the amazons persisted and compounded with the other common myth of a city of gold. Sir Walter Raleigh spent a good portion of his life, 20 years of so, searching for El Dorado. And in 1596, he said he had found it, in the same place in which the Amazons resided, next to the legendary lake “Parime.”

Cortes himself, on his departure from Cuba before he begins his conquest of the Aztecs is given a set of instructions that includes to “inquire where and in what direction are the Amazons.” During the conquest the stories are not forgotten, only developed upon by new authors who now wield the power of the printing press that has been around for a little over half a century now. As the conquistadors conquered the Aztec empire and came upon the incredible city of Tenochtitlan, one Spanish chronicler remarked that the Spaniards “could not help remarking to each other, that all these buildings resembled the fairy castles we read of in Amadis de Gual.” Adamis de Gual being the hottest new novel published in 1508 by Montalvo.

Following the success of his first novel, Montalvo publishes a second novel in 1510, Las Sergas de Esplanian which features stories of Amazonian women living on an island filled with gold.

When the conquest comes to an end, Cortes wondered if there was to be more to be found in these lands. Cities of gold and the Amazons as read about in Montalvo’s book. He sends one of his most trusted men to “visit the towns and people of those provinces and to bring me all the reports and secrets of the land that he might learn,” and what he comes back with cannot excite Cortes enough. Gonzalo de Sandoval comes back with an abundance of pearls, but this is not what most interests Cortes.

Cortes sits down immediately to write a letter back to the Spanish crown. He writes: “…there is affirmed to be an island inhabited by women without any men, although at certain times they are visited by men from the main land; and if the women bear female children they are protected, but if males they are driven from their society. This island is ten day’s journey from that province, and many have gone there and seen it. They also tell me it is very rich in pearls and gold; respecting which I shall labour to obtain the truth, and to give your Majesty a full account of it.”

An island of women without any men where there is an abundance of gold. Yes, there are many stories of the Amazons but this one sounds suspiciously similar to the one that appears in Montalvo’s, Las Sergas de Esplandian. “Know that, on the right hand of the Indies, very near to the Terrestrial Paradise, there is an island called California, which was peopled with black women, without any men among them, and they lived in the manner of the Amazons. The island everywhere abounds with gold and precious stones . . . In this island called California are many Griffins, on account of the great savageness of the country and the immense quantity of the wild game there . . . Now, in the time that these great men of the Pagans sailed (against Constantinople) with those great fleets of which I have told you, there reigned in this land of California a Queen, large of body, very beautiful, in the prime of her years…” The Queen was Queen Califa.

Now Cortes is determined to find California. Between 1532 and 1539 he would pour a substantial amount of his wealth into expeditions searching for the island. All of that was yet to come though. The Spanish Crown was not particularly excited by Cortes’ letter, although they did like the sound of gold and pearls. They were more concerned with the expansion of territory and power of the conquistador and so instead of being sent to explore the coastline, he is sent to Honduras to supress a revolt. By the time he was back in Mexico, he was wrapped up in a number of controversies ranging from brutality towards both the Spaniards and the natives to installing corrupt officials. A judge, Luis de Ponce was sent from Spain to investigate the situation. The man sent to investigate Cortes died of illness 15 days after arriving in the New World. His named successor lasted a little longer: 7 and a half months. The death of one judge could be seen as unfortunate but two in such short succession looked suspicious. Cortes was accused of foul play with the newly arrived Guzman doing much of the finger pointing. Cortes’ exploration efforts would have to be put on hold while he went to Spain to defend himself.

This left the explorations open for Guzman who wrote to the Spanish crown in 1530: “I shall go to find the Amazons, which some say dwell in the Sea, some in an arm of the Sea, and that they are rich, and accounted of by the people for goddesses.” He found nothing though. Only terrified women and children and settlements devoid of men who had fled to the mountains, hearing that the brutal Spaniards were coming. Cortes’ rival, Guzman had failed to find California, but this did not dishearten Cortes, if anything it came as a relief as now he could be the one to find the island of gold.

He returned from Spain in 1530. He had not been welcomed as he had expected by the Spanish monarchs but he had succeeded in convincing them of his innocence as well as managing to get them to grant him the title of “Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca,” essentially giving him control over a large and wealthy portion of South Western Mexico. And with all this money, he used a large portion to search for California. He sent off his first expedition in 1532 which ended in disaster. One ship mutinied and the other disappeared without trace.

The following year two more ships were sent to search for the first that had gone missing, as well as the illusive island. Again, the voyage was a disaster. The two ships got split up. One mutinied and the other quickly ran out of supplies and had to return back south. The ship of mutineers had made a discovery though. They had landed on an island, rich in pearl fisheries but inhabited by fierce natives that killed the leader of the mutineers. The rest of the mutineers managed to escape across the gulf where their ship was confiscated by Guzman who controlled this territory and intended to use the ship for his own explorations.

Cortes wrote a letter to the Audencia, now no longer led by Guzman, complaining that Guzman had stolen his ship and intended to explore lands coveted by him. The Audencia responded by ordering Guzman to return the ship and told both men that they were not to explore the area any further.

However, Cortes had a burning desire to see this pearl island for himself. Could it be the fabled island of gold? And so in 1535 he went on an expedition that he took part in himself to the tip of Baja California with 380 soldiers and settlers to establish a colony. They landed at present day La Paz and started their settlement. The settlement was a logistical nightmare. Getting supplies over from the mainland was difficult and dangerous. Cortes took part in one of these supply runs himself in which, during a storm, the ship’s pilot died and so Cortes himself had to steer the ship to safety. When he came back, he found that 23 of the colonists had already starved to death. Cortes, not wanting to witness the misery, sailed away to explore more of the coastline. He found very little of note, but this journey was significant in that it is one of the first accounts in which the name of the peninsula is written down as California.

On his return, a letter was waiting for him, calling him back to the mainland since he had been told not to carry out this expedition. He obliged, probably quite enthusiastically given the circumstances, and left the colony in the hands of Francisco de Ulloa who had been in charge of the colony while Cortes had been away. Ulloa hastily abandoned the settlement and returned to the mainland shortly after Cortes left.

The whole ordeal so far had been a disaster for Cortes, he had lost ships, men and a lot of gold funding these expeditions. Perhaps this would have been the point that he would have called it a day in his explorations of this new island, if it were not for the arrival of a very peculiar conquistador to Mexico City in 1536.

Alvar Nunuz Cabeza de Vaca’s story is an incredible one and not one I have enough time to go into detail on here. Essentially, he and his crew had been shipwrecked in Florida, and over the course of 6 years he and 2 other survivors had travelled through unknown territory across today’s United States before coming down the coastline of the Gulf of California. Upon hearing this incredible story, Cortes sat down with Cabeza de Vaca and listened as he told stories of well populated lands with wealthy cities, lying to the north of Mexico where no other Spaniard had been before. What made these claims more credible were the stories arriving in Mexico that a distant cousin of Cortes had managed to find a wealthy and advanced civilisation similar to the Aztecs in the land of Peru.

So, in 1539, Cortes funds the journey of his friend Francisco de Ulloa to travel the coastline of Mexico, find the tip of the island of California and report on the great cities of gold that he might find. Ulloa sailed north up what he had now named the Sea of Cortes until he reached what was not the tip of an island, but the mouth of the Colorado River. Unable to enter the Colorado River he proceeded around Baja California before returning back to the mainland.

Soon after Ulloa had set sail, the Viceroy of New Spain sent his own expeditions to verify the stories of Cabeza de Vaca. Hernando de Alcaron was sent up the coast and did manage to enter the Colorado River, reaching as far as Yuma. Marcos de Niza led the land campaign and claimed to have seen a great city like Tenochtitlan from a distance, although this later turned out to be nothing but a few mud structures.

From Alcaron’s expedition, an accurate map of Baja California could be produced for the fist time. There are a few interesting things to note about this map. Firstly, there is the city of Cibola noted at the top, the fictional city of gold that turned out to be a great disappointment for the Spanish. Secondly, is the name California, which is the first time it appears on a map and is maybe quite surprising that the name of a fictional island has stuck because thirdly, this is quite clearly a peninsula and not an island. Whether the name had simply stuck after being referred to that way for so long, or if it was the Viceroy’s idea of some cruel sarcasm against Cortes as the land was clearly not an island filled with gold and Amazons, we do not know. But the question remains, how did we end up with California as an island?

To understand this, we need to look at how people at the time viewed the earth. Very shortly after Columbus arrived in the Caribbean it was realised that these islands were not part of the islands in Asia and that South America was in-fact a whole new landmass and continent, previously undiscovered. There was one question remaining though that many wondered, which was if the Northern part of the Americas was attached in some way to Asia. Despite being debated amongst cartographers and scholars, the prevailing opinion was that they were indeed connected in some way.

If the continents were indeed connected, there was the possibility that a strait existed, leading up to China, referred to Marco Polo as Cathay, a land filled with riches and merchants willing to trade. For Spain, finding this passage was a priority. Cortes wrote to Spain: “Your Majesty may be assured that as I know how much you have at heart the discovery of this great secret of a Strait I shall postpone all interests and projects of my own, some of the highest importance, for the fulfilment of this great enterprise.” The Gulf of California had reached a dead end and in 1542 an expedition was sent up the Pacific coastline of California but found no passage and northing in particular to note that could be exploited by the Spanish. California was claimed by the Spanish and then largely forgotten about. Although some people continued to wonder about the Colorado River. Especially in the account from Ulloa who had failed to enter the river but had marvelled at the scale of the estuary. Could this in some way be the more sought after strait, leading to China? Whatever. The Spanish crown seemed disinterested and shifted their focus to more pressing matters.

The Spanish had given up on seeking a passage, but the English were as keen as ever to find one. Ever since Magellan passed through the straits of Tierra del Fuego in 1520, the English believed a Northwest Passage existed that would take them through Canada to the Pacific. Many at the time believed that the earth was balanced. What existed in the southern hemisphere must have its equivalence in the northern hemisphere as well. This idea had been thought of by the Greeks and explains why Antarctica appears on maps centuries before its discovery. If there is an arctic, there must be an Antarctic. If there is a passage at the Southern tip of the world, there must be a passage at the northern tip.

All through the 16th century people were convinced that transit through the northwest passage was possible and that the place it terminated was a place called Anian. Anian took many forms, some maps displayed it as a landmass, others showed Anian as a strait. Different access points were attempted from the east coast of North America but to no avail. But what if they tried from the West?

It just so happened that Sir Francis Drake was making his circumnavigation of the globe and in 1579 had made it to the West coast of North America. Drake made landfall in Northern California, (or Oregon, it’s complicated) and then travelled north searching for a passage that would take him back to England. The further north he went, the colder it became and the thick ice forced him to turn around and he makes his way home through the straits of Magellan. Or did he?

Well yes, but the rest of the world didn’t know that. On Drake’s return, the map he produced is locked away only in the possession of the Queen, only to be seen by a handful of select people. This map is a replica, the other burnt in a fire and so that’s why the debate over where Drake landed is so hard to determine. All of the sailors that sailed under Drake were sworn to secrecy about the route under the penalty of death.

And so, the rumours began. That Drake had managed to find a shortcut back to England. That he had done it by sailing through the Strait of Anian. That he had found the strait by sailing up the Gulf of Anian.

At the same time, there is the possibility that another rumour was brought back, perhaps started again by the Spanish themselves, that California was indeed an island. Spain was involved in a kind of cold war with England at the time, Queen Elizabeth was funding privateers like Drake to act as a thorn in the side of the Spanish. Drake had gone and claimed the northern part of California for England, naming it Nova Albion at a time when Spain was struggling to maintain her territories. Spain had little claim to the land in the northern region of Alto California and was doing nothing to maintain the claim on the Southern region, around modern-day Los Angeles. If the English decided to establish a permanent settlement at Nova Albion it would be a massive blow. However, if what Drake had actually landed upon was the island of California, well Spain had a much more solid claim to those lands.

To add to the rumour is the curious decision regarding the name “Nova Albion”. Us Brits have many names for different parts of the British Isles. Today, there is of course the invidual nations of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland that make up the United Kingdom. Which is part of the British Isles. Which is made up of the islands of Great Britain and the island of Ireland. But Albion, is often used to refer to the island of Great Britain in a poetic sense. This may not be the most compelling evidence but it adds to the mystery at the time when all of these rumours were flying around.

The Spanish were furious that Drake had managed to pass through their territories with such ease. They felt vulnerable at a time where they essentially had a monopoly on the new world. They began to increase their defences and double down on their claims, this included in California.

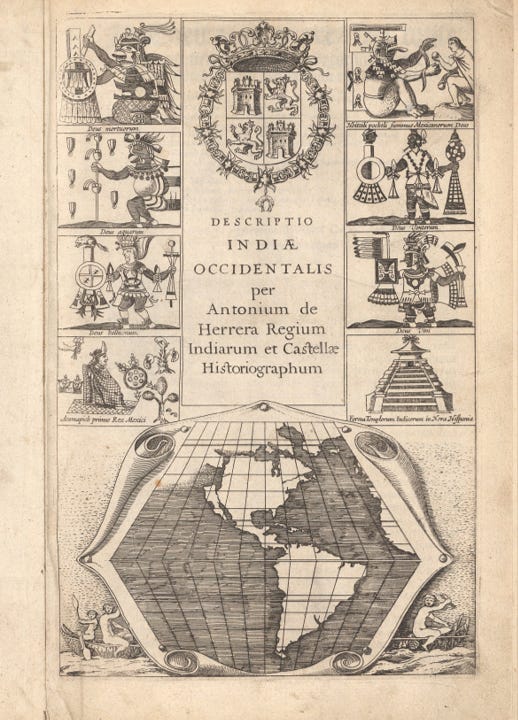

In 1602, Sebastian Vizcaino is sent to map the coastline of California and to see if there is a suitable location to establish a port, so that a trade connection could be made between Spanish territories in South America and Asia. Vizcaino returned with a rather detailed map of the coastline and suggested a port should be established at Monterey.

Documenting much of this rather uneventful voyage was a Friar by the name of Antonio de la Acencion. And he, thought that the idea of a port at Monterey was the plan of the devil. So he decided to write to the king suggesting that a port be established at Cabo San Lucas, called San Bernabe back then.

Fray Antonio puts forward the argument that the area is rich in pearls as well as having nearby settlements on the mainland in which people are keen to move and settle in a new location nearby. What Fray Antonia really wants though is quite simple. He wants to save people. He had encountered the indigenous people of Baja California and concluded that if a settlement be established at Monterey, then the souls of the people at San Lucas would be dying without having received the Holy baptism.

Fray Antonio also puts forward the possibility that with a settlement at Cabo San Lucas, it would be easy for explorers to travel up the Gulf of California to investigate the fabled strait and reach Spain. But it doesn’t matter. Because, before the letter from Fray Antonio even arrives on the desk of the king, the king of Spain cancels any project to establish a port on the West Coast of California.

Fray Antonio doesn’t take the news well. He’s frustrated that nobody is taking an interest as he is in the lands of California and its people. 7 years after going on his voyage he decides to write again about what it was that he saw. The account is far from neutral. He emphasises the beauty of Cabo San Lucas and the suitability of the harbours to be found in Baja California. He also writes that looking out on the Gulf of California he can see it “extends to New Mexico, passes the Kingdom of Quivira, and terminates at the Strait of Anian, by which one can find passage and navigation to Spain…” He goes on further to write: “I hold it to be very certain and proven that the whole Kingdom of California discovered on this voyage, is the largest island known or which has been discovered up to the present day.”

Fray Antonio doesn’t write only about his own, heavily embellished travels, he also compiled stories from other expeditions. One in particular to note is that of Juan de Onate, who was tasked with exploring the region surrounding the Colorado River in 1604. Accompanying Onate is a barefoot Friar, Fray Escobar. He talks about the things he has seen. Let me know if any of this sounds familiar, he mentions a nation that would sustain themselves on food through smell alone, a nation of people that slept underwater, another nation that slept in trees. My personal favourite, “another [nation] whose men had virile members so long, they wrapped them four times around the waist, and that in the act of generation the man and woman were far apart…” Then there was the nation of people with one foot and of course, the warrior women that lived without any man and oh my goodness we seem to be going backwards!

These ideas of California as an island of gold, of humanoid beasts and warrior women was old by this point. The Viceroy of Spain wrote back to the King: “I cannot help but inform your majesty that this conquest is becoming a fairy tale.” When advising on whether further expeditions should be sent to the region he said: “If it should prove to be an appropriate place, it might be possible to explore from there the interior [“New Mexico”] or island of the Californias, which has always been much sought.”

And just like that, very casually and anticlimactically, we have perhaps the highest official in the New World, writing to the King of Spain, that California is indeed an island.

Fray Antonio spent the rest of his life trying to convince people that California was indeed an island, and that it was where the strait of Anian was to be found. His works never reached widespread notoriety, but it was of the interest to a number of scholars, namely Juan de Torquemada. Torquemada omitted much of the most outlandish claims by Fray Antonio, including an entire chapter named: “Chapter XV, in which is treated of how the Kingdom of California is not connected with that of New Mexico, and in which the reasons are given to prove it.” But what does stay in is the description of the Gulf of Mexico on that voyage with Vizcaino, that the gulf “extends to New Mexico, passes the Kingdom of Quivira, and terminates at the Strait of Anian, by which one can find passage and navigation to Spain…”

In the latter half of the 16th century, war broke out between Spain and the Netherlands, known as the eighty years war. The Dutch very quickly became a formidable force, capturing Spanish treasure ships, and on one occasion, an entire Spanish treasure fleet. It was not only gold and silver that could be found on these ships though. Navigational charts, like the map showing Drake’s voyage, were kept secret from enemy powers.

And in 1622, on the front of a Dutch encyclopaedia, we see for the first time an island off the coast of North America, the island of California. Like fake news on Twitter, it gets retweeted by the English, and then again by the French. And like fake news of today, once it has taken a hold, its really difficult to reel back in again.

In 1739, the Jesuit Historian Miguel Venegas is tasked with producing the definitive work on the history of Baja California and he comes back and said that it is almost certainly a peninsula. The problem is that Miguel Venegas doesn’t know how to trim the fat. His writing style is long and dry, and nobody wants to publish the 600 pages he’s written. It isn’t for another 18 years that another Jesuit historian sits down with Miguel Venegas’ work and starts to cut all of the unnecessary junk, producing the much-abridged section on California, published as Noticia de la California.

In Europe the depictions of California started to phase out but further afield, in places like Japan, it took longer for changes to be made. In fact, the California gold rush had started 17 years prior, and the Japanese were still producing maps, showing the area as an island. It turned out in a rather strange coincidence that the island of queen Califa was in-fact filled with gold.

We no longer believe in the lion-headed man that protects our tribe from the floods, that cotton comes from a plant blooming with small sheep, or that outside of our kingdom there are bizarre humanoid creatures and tribes of fierce warrior women. But we are still influenced by stories. Some of these stories, like Mandeville’s Travels, function as a way to separate us from those outside of our kingdom. But we should remember that many of these stories, are just fairy tales.