Harald and the Hafrsfjord

What Norway’s origin story can teach us about power, propaganda, and long hair.

I recently visited the port of Stavanger, Norway.

A short bus ride from the harbour brings you to Hafrsfjord, which translates to “the male goat fjord.”

Set into the rocks by the water are three enormous swords. I’m 6 foot 4 (194cm), and they still made me feel short.

Then again, I’ve felt short this whole trip. I think I’m about eye-level with your average Norwegian eleven-year-old.

But why are these swords here? And what story are they trying to tell?

Introduction

These enormous swords mark the site of a legend.

It was here, in the year 872, that a young warlord named Harald is said to have defeated his rivals and united Norway under one crown.

The largest of the swords represents Harald, and the two smaller ones, the petty chieftains he defeated.

The story of Harald’s victory is the story of Norway’s beginning.

The Norwegian sagas present him as a mighty pagan who ultimately embraces Christ, neatly tying the birth of the nation to military might and Christian destiny.

He becomes a righteous founder. The man from whom all future kings and queens of Norway could trace their lineage.

But from the moment Harald’s victory was over, the story has been told and retold. Sometimes to glorify the crown, sometimes to challenge it.

This monument, and the saga that inspired it, aren’t really about the 9th century at all.

They’re about something else.

They’re about the fine line between history and myth - and how nations invent their past.

The Official Story

So let me tell you a story.

About a young man named Harald, who fell in love with a woman who would only marry him should he manage to conquer all of Norway.

And so, Harald made his vow to do just that, as well as a vow to not cut or comb his hair until the task was done.

He raised an army and for ten years fought across all of Norway to consolidate his rule. His greatest victory came here at Hafrsfjord in 872 when his rivals joined together to try and defeat him.

Once the task was complete, Harald cut his hair and became Harald Fairhair. He had gone from wild warrior to civilised king.

For the next several decades, he ruled all of Norway - fathering many sons from which the royal dynasty would stem.

This is the official story.

But it’s not the only one.

The Sagas

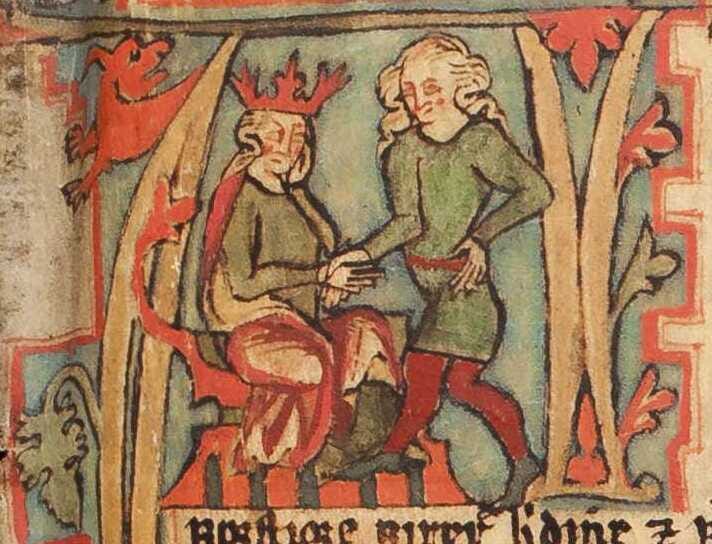

What we are told about Harald comes mostly from the sagas - oral histories passed down and eventually written in Iceland 300 years after Harald’s supposed victory.

We have the Norwegian kings’ sagas, written for the monarchy in Norway, and the Icelandic sagas giving an Icelandic perspective, which were much more scathing.

After all, Iceland was a land settled by those who had fled Harald’s taxes and centralised state.

At the time these sagas were being written, the Norwegian crown was actively trying to bring the “Viking” territories in the Atlantic under its control.*

And somewhere in the middle we have Heimskringla - the most influential and most interesting of the Harald sagas.

Read by the Norwegian crown, it could be seen as a work of praise.

Read in Iceland, it became something more subtle. A work of propaganda in the Icelandic Republic, full of critiques that only needed to be read between the lines.

* I put “Viking” in quotation marks because Iceland was uninhabited before settlement, and those who arrived were a mix of ordinary Scandinavians and people from the British Isles. Some may have gone viking, but most weren’t raiders - they were farmers, families, and fugitives.

Snorri

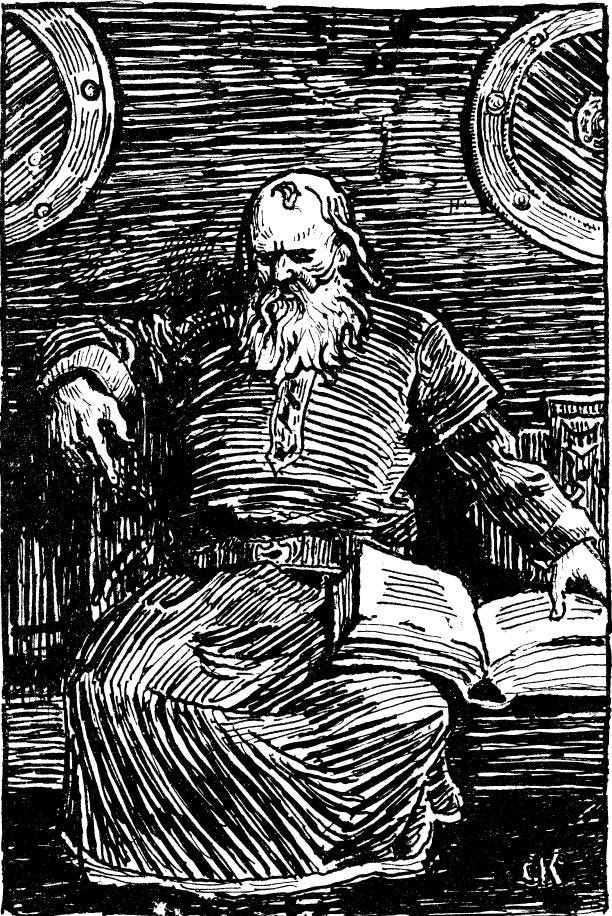

Well… who even wrote this famous saga?

No one signed their name, but it’s widely believed to be the work of poet and politician Snorri Sturluson, a man with a very complicated relationship to the Norwegian crown.

Born in Iceland, Snorri spent a lot of time in Norway, working directly for the crown and agreeing to help expand its influence in Iceland.

To say he was an unreliable agent in Iceland would be an understatement. He promoted the Norwegian crown but also sought to boost his own political power, leading to bloody feuds, betrayal, and eventually King Haakon’s decision to have Snorri assassinated.

But it was before the relationship turned sour that Snorri wrote Heimskringla, trying to delicately walk the line between royal praise and Icelandic independence.

Gyða

The critiques he made were subtle - but enough to leave openings for others to pounce.

A good example of this is Gyða, the woman Harald wishes to marry.

In Snorri’s version, Harald doesn’t ask to marry her. He sends messengers to offer to take her as his frilla, his concubine.

Gyða refuses.

She doesn’t directly address the frilla offer. Instead, she says she’ll only give herself to a man who rules all of Norway. She sets the terms.

Harald takes the challenge. He conquers Norway. Then, after the battle of Hafrsfjord, he sends for her again. And Snorri tells us: he lay with her. That’s it. No wedding. No happy ending. She disappears from the story.

Now you might be able to read between the lines here, but this just a small part of a very long saga that for the Norwegian Crown would have seemed nothing more than undying praise of Harald and his kin.

You’ll also notice it is in the subtleness of what Snorri does not say rather than what he does.

He would have made a fantastic spin doctor in the 21st century. And like Dominic Cummings, it’s very difficult to tell what he actually wants out of all of this. Perhaps above all, just power and influence be it from the crown or his countrymen.

Anyway, he had left enough open that the Icelandic sagas would interject in this moment that Harald sends for Gyða as his concubine.

They paint Gyða as a strong and independent woman, who scoffs at Haralds offer and explicitly states she will not settle to be his concubine.

She is sent for and used by Harald for reproduction.

But later Icelandic versions would make out Harald as even more of a scumbag, driving home the point that the woman who imagines the Kingdom of Norway was immediately cast aside by the monarchy once the conquest was over.

The crown responded with its own, rather unconvincing, rewrite. In one version, Gyða is renamed “Ragna,” and Harald becomes a feminist king who marries her, reforms the law to protect women, and declares her his only wife.

A Story Too Perfect

Now you might be feeling quite sorry for poor Gyða around this point but don’t worry. She probably didn’t exist.

There are things that in the historical context don’t make much sense, like the autonomy at which she can negotiate her marriage when, in such a patriarchal society, it was usually the father of the bride who discussed such terms.

But beyond that the story is just too… perfect.

Gyða gives Harald a moral pretext. The mass violence that Harald commits after his oath isn’t his lust for power, it’s about love. You can’t be against love, right?

Harald’s Hair

Apologies for going full English literature student on you, but everything in Harald’s story is symbolic of a typical origin myth - all the way down to the second oath he makes to Gyða, about his hair.

As a fellow long-haired man, it feels a little strange to analyse Haralds decision not to cut his hair but this and many of the ideas I’m presenting about are borrowed from Bruce Lincoln’s Between History and Myth.

Lincoln says that to stop cutting one’s hair for a prolonged period of time is to defy norms. To abandon ideas of tradition and show no concern for what people construe as civilised.

Lincoln really hammers this point home by including around twenty images of famous long-haired rebels from history from Alexander the Great to Rasputin.

And maybe he’s got a point.

The idea is that Harald transforms during this period. He becomes wild in the years of his conquest.

That wildness can be seen as a way of justifying the brutality of his actions.

And once the violence has ended, he becomes “civilised,” cutting his hair and going from shaggy Harald to Harald Fairhair.

Conclusion

So what actually happened here at Hafrsfjord?

We don’t know. We can never know. That’s the thing about history.

If we had to record the events of last week, we’d probably do a terrible job of it.

Switch from Fox News to CNN and you’re already living in two different realities.

But you can learn a lot about the people who write history based on the stories they tell.

That’s what Bruce Lincoln argues breaking down the different kinds of history: critical, official, revisionist, epistemological…

He favours the epistemological kind - history that is honest about its limits. That says: here’s what we know, here’s what we don’t, and here’s why it matters.

Left in the hands of those writing the official histories and revisionists, the past can be used as a dangerous tool for power.

Lincoln makes the more than reasonable case that in an ideal world, we should strive to tell history in a way that acknowledges our limitations. And I agree with him. I find it incredibly frustrating to see how history is used by those in power.

But there’s still a place for stories. For myths. And for media that takes more than a few liberties with historical accuracy - because it’s the stories that get through to people.

It’s just important to remember that these are stories.

And we have to ask ourselves:

Why is this being told?

And who is telling it?

Interesting, I had heard of Stavanger because it is home to one of the best brass bands in the world, currently ranked 13th!