Frozen in Time: The Children of Llullaillaco and the Inca Ritual of Capacocha

This is not just a story of death, but of belief, devotion, and the Inca world beyond our understanding

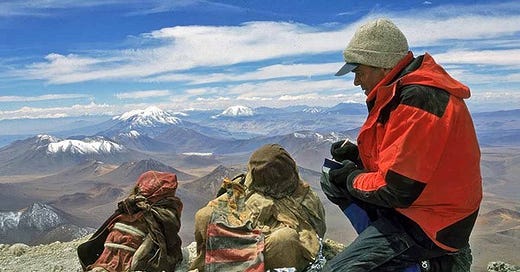

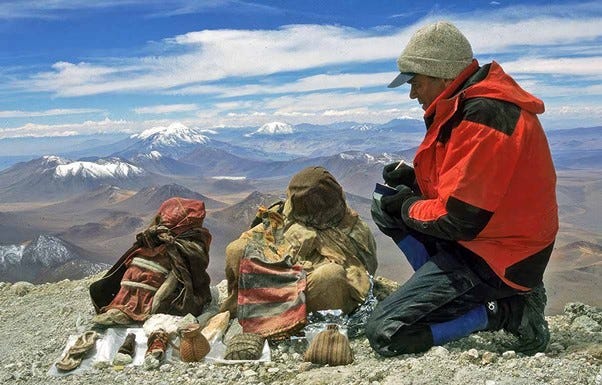

On February 26, 1999, a multidisciplinary team led by archaeologist Johan Reinhard set out from the Argentine city of Salta, heading toward the towering Llullaillaco volcano. Their mission? To search for Inca ritual sites hidden among the Andean peaks.

After a gruelling ascent through treacherous terrain, they reached the 6,000-meter summit on March 10, battling thin air and temperatures as low as -37°C. What they found there would change our understanding of the Inca world forever.

Three perfectly preserved mummies—buried in a frozen tomb for over 500 years.

They would come to be known as The Children of Llullaillaco—a discovery unlike any other.

Capacocha

The Children of Llullaillaco were part of a ritual sacrifice known as Capacocha which was practiced throughout the Inca Empire until its fall and can be traced back to the Moche people as far back to the 1st – 4th centuries CE who left pottery depicting human sacrifice. The ritual was performed in times of crisis as well as to seek the good health of the Sapa Inca and cure him of any illness that may have befallen him. What we know about Capacocha comes from the archaeological sites found as well as written Spanish sources from the likes of Cobo, Acosta and Betanzos.

Spanish chroniclers showed a high level of interest in understanding the capacocha. The information they provide is valuable but not without its flaws and clear exaggerations. The Spaniards recorded that thousands of children were sacrificed in this ritual of capacocha, yet archaeologists have found only 150 of these mummies across all Andean cultures. Its also important to remember that these Spaniards were looking on at a strange and unfamiliar world through the lens of their own Western ideals. What is written down as an observation is often an interpretation.

The Spanish chronicler Betanzos wrote that the children selected for the capacocha were “mourned” in their respected communities but to say so is a fundamental misunderstanding of the Inca worldview. Because for the Inca, biological death was a signal only for a change of state. A transition of the soul or mallqui between different planes or pachas.

This does not make the act of human sacrifice any less shocking to you and I. Nor did it make it any less terrifying to those who were selected to take part in the capacocha. But understanding how the Incas viewed death will give us insight into why this seemingly brutal act was carried out.

The Inca Religion

Andean religion is animistic, that is to say every person, animal, plant, mountain, celestial body, atmospheric or natural phenomenon has an immortal soul. Souls that upon death change their state between different planes. There was no concept of final judgement, salvation and damnation, no heaven and no hell. It seems from the sources and material culture that these planes ran parallel to one another.

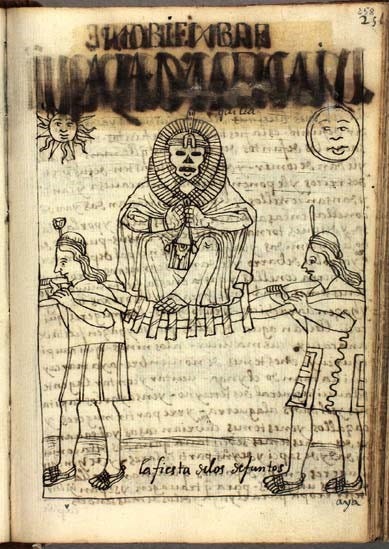

At the centre of the Inca religion was the cult of ancestors which focused on the continued presence of the diseased in Inca society. Those that had passed were not “gone” but lived on both spiritually and physically, meaning that the mummified family members were continually honoured through festivals such as the Aya Marcay Quilla where the mummies were dressed and paraded through the streets as well as offered food, coca, textiles and chicha, a type of corn beer. In this way death, at least the biological death, was celebrated and brought communities together.

The children of Llullaillaco would become part of this ancestor cult, not destined to die on top of the volcano, but instead be transformed into messengers of the Inca elite to carry their requests to the gods.

Capacocha differed though from other rituals that took place as part of ancestor worship. For the children of Llullaillaco there would be no second funeral, no in situ offerings of chicha and coca due to the remoteness of their final resting place, however they would still be seen as sacred objects or symbols with an important role in the entire Inca community, not just their ayllu, which is their family and line of ancestors.

The children became “natural” mummies as opposed to the embalmed ancestors found at the Aya Marcay Quilla. The Inca had not intended to preserve the bodies so perfectly, but the mixture of volcanic ash, sub-zero temperatures, and humidity halted the natural decomposition process. The volcanic ash that settled on the bodies kept bacteria away from the skin and preserved moisture, causing a chemical change. The acids in the fat under the skin rose due to the humidity and maintained the excellent state of preservation for centuries. All of this, combined with a layer of ice that sealed the tomb from the air, created the ideal conditions for preservation, such as low atmospheric pressure, low humidity, low temperature, and thermal stability in an aseptic environment, further slowing decomposition.

The Protaganists

La niña del rayo (The Lightning Girl)

At the time of her sacrifice, she was just six years old. She was found seated with her legs bent, hands resting gently on her thighs, and her face tilted upward toward the sky. Her eyes remain closed, and her mouth is slightly open, revealing her teeth. Her straight hair is styled into two small braids starting from her forehead.

It is likely that, due to her high status, symbolic beauty, and possibly her ethnic identity, her skull was intentionally shaped from a young age to develop a conical form—a common practice among the Inca elite.

She is known as "The Lightning Girl" because, at some point after her burial, a lightning strike burned part of her face, neck, shoulders, and arms, along with parts of her clothing and burial offerings. The most widely accepted theory is that the lightning was drawn to a ceremonial silver plate she wore on her forehead.

She was dressed in a light brown acsu (a traditional Andean dress), cinched at the waist with a multi-coloured sash. Over her shoulders, she wore a lliella (a type of mantle), fastened at the chest with a silver tupu (a decorative pin). Her hair was adorned with a metal plate, and a thick dark woollen blanket covered her entire body. A second, lighter-coloured blanket with yellow embroidery wrapped her burial garments.

As offerings to the gods, she was accompanied by gold and silver figurines, ceramics, food, textiles, and mullu (Spondylus shells, considered sacred by the Incas).

El niño (The Boy)

The boy was around seven years old at the time of his death. His fists remained clenched, his face was turned away, and his eyelids were half-open. Like The Lightning Girl, his skull had been intentionally shaped into a conical form.

He was dressed in a brown and red lliella that covered him from his shoulders to mid-body. Beneath it, he wore a red garment and light leather moccasins with brown wool appliqués. His short hair was adorned with a white feather headdress, held in place by a wool sling wrapped around his head. He also wore anklets made of white-furred animal skin and a silver bracelet on his right wrist.

Seated on a grey uncu, his face was turned east toward the rising sun. His head rested on the lliella, which bore a large stain of blood and saliva, suggesting a violent death caused by an internal injury.

In front of him, an elaborate burial scene depicted llama caravans led by finely dressed men. These figures, arranged in careful rows, symbolized caravanning and herding, key roles in Andean society. His burial, the only male among the three, reflected the importance of these activities in the world he was leaving behind.

La doncella (The Maiden)

Although known as one of the "Children of Llullaillaco," The Maiden was not considered a child in Inca society. At approximately fifteen years old, she was already seen as a young woman. She was found seated with her legs crossed, her arms resting on her abdomen, and her face turned northeast. Her hair was braided into small plaits, a common practice in many Andean villages, and her face was painted with red pigment. Fragments of coca leaves were found around and inside her mouth, suggesting she was chewing them at the moment of her death.

She wore a light brown acsu, cinched at the waist with a sash decorated with geometric patterns in light and dark tones. Over her shoulders, she carried a grey lliella with red borders, fastened at the chest with a silver tupu. A set of bone and metal pendants was placed near her left shoulder. She also had a small cranial trauma, though there is no evidence of violence at Llullaillaco. Like others who took part in capacocha, she vomited shortly before her death.

The Maiden may have been an aclla, a "chosen one" trained in rituals and textiles from a young age. If so, she would have lived in the Acllahuasi, the House of the Chosen, under the guidance of mamaconas. By the age of fourteen, girls like her were assigned their roles—married to Inca nobles, dedicated as priestesses, or, as in her case, selected as sacrificial offerings.

The Body Analysis

The extraordinary state of preservation has allowed for analyses that, in other cases, have not been possible, allowing archaeologists to uncover mysteries surrounding the ritual of capacocha.

One of the best forms of genetic data we have is the intact hair follicles of the mummies, especially that of the maiden as her longer hair means that her diet can be analysed over approximately 2 years using a stable isotope analysis of carbon and nitrogen.

The results from this analysis suggest that the maiden had consumed a diet typical of an Inca peasant two years prior to her death, however one year before her death there is an increase in consumption of animal protein and C4 plants, most likely corn, suggesting an elevation in status a year prior to the sacrifice which can be assumed was the time in which she and the other two were selected for sacrifice.

The length of the boy and the lightning girl’s hair means we can see only what their diet was in the year leading up to their sacrifice which also indicated consumption of C4 plants and animal protein.

A different analysis using high-performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry on hair sample from all 3 children was used to try and assess the consumption of chicha and coca leaves before their deaths. Both products were always consumed in an Andean ritual context. And coca was, and still is, consumed as a way to alleviate the symptoms of altitude sickness.

The analysis showed that all 3 consumed coca and chicha, with the amount increasing as they reached the summit. But while the amount consumed by the younger two increased gradually, the Maiden’s consumption was extremely high in the last two weeks leading up to her death.

A CT scan even revealed that she had died with rolled coca leaves still between her teeth.

X-Ray scans on the lightning girl and the boy showed researchers that their skills had been intentionally modified but by collaborating with dentists, researchers have been able to answer questions about the abnormal tooth wear of the individuals. Dentists have suggested that the tooth wear is due to the grinding of the teeth, a sign of fear and prolonged distress and suggesting that the children knew that something was going to happen to them at the end of their journey.

The Journey

The journey for the three children began in Cuzco, perhaps with some kind of ceremony, before making the thousands of kilometres journey to Llullaillaco.

Llullaillaco had been chosen for its sacred importance. The landscape played an important role in the religion of the Inca with these “sacred places” known as huacas taking on a benevolent or malevolent character. Llullaillaco is the highest point in a vast region, an ideal place of contact between the pachas or realms and its slopes are home to numerous archaeological remains related to ritual practices.

The mountains and volcanoes of the landscape offered people water from springs and land for agriculture on its slopes. Often times they did not require much in exchange for these benefits which were not free. But every so often circumstance would have that the huacas would demand more from the Inca people.

Many consider the capacocha to be a way for the Inca people to atone for the government’s guilt regarding a particular issue or mishandling of events, often related to a severe political-economic crisis.

The journey the three children from Cuzco involved crossing the Atacama Desert, traversing the Salar de Punta Negra, and ascending one of the highest volcanoes in the world. To make the journey easier the group traversed the Inca roads that connected the huacas in the area and stayed in refuges known as tambos that were at regular intervals along the Inca roads, stocked with provisions for travellers.

The Spanish chroniclers tell us that the mothers of the children were forced to accompany the children on their journey and suggest that if they showed signs of sadness, then they would be punished since being chosen for the capacocha was a great honour. This would have been a key way in keeping the children calm in their approach to the huaca.

As the three children approached the volcano, they would have had different ideas for what was about to happen. The two youngest would have been easy to control the adolescent would have understood differently what was about to happen, especially if she was indeed an aclla and had seen and participated in several rituals throughout her life.

Coca contains relatively little of the cocaine we associate with the powdered substance, but despite this, the maiden had Charlie Sheen levels of cocaine in her system by the time she was summiting the volcano alongside the huge quantities of alcohol in her system. One hypothesis is that she was drugged in the last days of her journey as she feared her approaching death and may have attempted to flee her fate.

The journey to Llullaillaco was treacherous. The children had to endure extreme altitudes, sub-zero temperatures, and harsh terrain. If the Inca had wanted to perform sacrifices, wouldn't it have been easier to use adults instead? Why were children and adolescents specifically chosen?

The Spanish chroniclers suggest that children were selected for their purity and innocence, an explanation that has been widely accepted but deserves scrutiny. The Inca religion did not include concepts of sin, punishment, or final judgment, so what exactly did "purity" mean in their worldview? Was it a moral designation, or did it hold a different significance?

One possible answer lies in the status of the Maiden, who may have been an aclla—one of the "Chosen Women." Acllas were selected between ages 8 and 10 from across the empire and placed in Acllahuasi (houses of seclusion), where they were trained in religious and domestic service under the supervision of mamaconas (priestesses). By their mid-teens, they were assigned roles, either: Married to Inca nobles, dedicated as priestesses of the Sun, or Chosen for ritual sacrifice.

The acllas were often referred to as “Virgins of the Sun”, and their chastity was closely guarded—not for moral reasons, but because they were considered state property. Father Bernabé Cobo explicitly states:

“These maidens were carefully guarded not because of any concern for their personal morality but because they were dedicated to the Sun and to the Inca. To violate them was to rob the empire.”

(Historia del Nuevo Mundo, Book 13, Chapter 10)

This suggests that Inca purity was more about imperial control than moral virtue. The status of these girls as "untouched" was not a spiritual necessity but a political one—a means of ensuring their role in either elite marriages or religious service.

While the Spanish chroniclers’ claims of innocence and purity are appealing explanations, it is clear that the Inca concept of purity was deeply intertwined with status and control—not just moral virtue.

While the Inca selection process for capacocha is often framed in terms of purity and perfection, the reality appears to be more complex. Was the Maiden truly an Aclla, chosen for her symbolic virginity, or was she selected for other reasons? A curious detail challenges the assumption that she had spent years in an Acllahuasi: among her burial offerings was a lock of hair from a close maternal relative—a deeply personal relic that suggests she may not have been entirely separated from her family.

The Material Finds

What other questions might be raised when we look at the material finds? What do they tell us about the identity and status of these individuals?

In death, the children were given the same status and consideration as the highest in Inca society, reflected in the garments they were wearing. The Maiden is wearing high-quality cumbi textiles, reserved for nobles and religious figures. While not as high quality the other two are dressed in fine textiles, dyed with high status colours such as deep reds and yellows. The boy wears the wool sling wrapped around his head, an attribute of the Sapa Inca and the girls wear the jewellery typical of a Coya, an Inca queen.

In front of the boy was an offering of several pieces that put together made a scene. Human and llama figures of gold, silver and seashell were put together to represent llama caravans, led by men in fine clothing. Caravanning was one of the main male activities in the Andean world, along with herding, which is likely why the scene was represented only in the boy’s burial offerings.

The girls also had representations of activities that are predominantly female such as textiles and agriculture, suggesting an attempt to recreate some kind of a scene for the females as well, although it is not as evident.

Each child had a set of figurines placed near them dressed in miniature versions of elite Inca clothing. Some of the figurines also had feather headdresses and ethnic markers which may have represented the regions the children came from.

Then of course there are the objects associated with the coca and chicha consumption found nearby and we know that all three had consumed both these substances.

The clothing and funerary offerings found with the Llullaillaco children suggest that the children were elevated to the highest level of Inca status in preparation for the capacocha ceremony, but it is not necessarily the case that these children were born into noble status.

The Status of the Children

We have already seen that the Maiden was perhaps an aclla and the modifications in the shape of the boy and the lighting girl’s skulls has for a long time been an indication that they came from noble families. However, we perhaps need to reevaluate this conclusion given that while elite individuals often had cranial modifications, not all those with cranial modifications were elite and could instead reflect regional identity.

We have already seen evidence in a change of diet for the maiden and it is not unlikely that this could have been the case for the other two. When looking at stable isotope analysis for mummies from both Llullaillaco and Aconcagua, John Verano comes to the conclusion that:

“Stable isotope analysis of sacrificed children suggests that while some had consistently high-status diets, others showed a marked improvement in nutrition after selection. This suggests that some were not born into elite families but were ritually elevated before sacrifice.”

This is also backed by some of the Spanish chroniclers who suggest that children were taken from both the families of the elite as well as offered up by local rulers or communities:

“They would take children from different parts of the empire, selecting the most beautiful and perfect, and they were sent to Cuzco where the ceremonies took place. Some of these children were of noble blood, while others were given as offerings by the communities.”

Age and Gender

Its still not fully clear as to why certain children were chosen. The chroniclers often draw to the idea of beauty and perfection and more traditional archaeology has cited their purity, whatever that may be, as a reason. The status of the children certainly played a role but what is not often discussed is the gender of the children selected for capacocha.

At Llullaillaco there are three children, two female and one male but we see an overwhelming trend towards female sacrifices over male. There is a cut off point for male participation in the capacocha, while we do see adolescents like the maiden selected for sacrifice. This goes someway to explaining the bias towards females being selected if the maiden is indeed an aclla and only acllas may be selected after a certain age.

Another theory put forward is that the females were sent to serve Pachamama, a central figure in the Inca religion that predates their existence and still survives today in Andean culture. The realm of the gods reflected that of the realm of earth on which the acllas were to serve the Coya. Now the acllas were sent to be sent to another realm to serve the Pachamama.

But if girls were so favoured, why was a boy included in the Llullaillaco sacrifice? And why was his death so different? The boy poses a number of interesting questions about the capacocha. Firstly, there is the elaborate caravaning scene mentioned but most curiously, the circumstances of his death differ from that of the other two.

The females were heavily sedated by the time they reached their tombs. One of the most ominous things about these mummies when you see them is the fact that they appear as if they are merely sleeping. The girls are in relaxed positions, having died in relative peace from exposure to the elements, being so heavily drugged that they would not have been aware of their surroundings.

The boy on the other hand is tied up and in a more artificial position with his arms stretched out and tied to his legs with a rope. Forensic experts found a stain on his clothes where his head rests that suggests it is saliva and blood, confirming the boy died from an internal injury.

There are numerous theories as to why the boy died under different circumstances than the females. He had not been as heavily sedated as the females and so perhaps he resisted or did not fully cooperate with the ritual. Some have suggested that he was an offering to a more violent deity of the Inca pantheon or perhaps even a secondary or lower-status sacrifice than the females due to less elaborate funerary goods.

There’s still a lot to be uncovered about the capacocha, especially when it comes to the considerations of gender and the archaeology of childhood. For a long time, archaeologists have lumped these two into one category of the “women and children”. Portraying them as observers of the world around them as opposed to having their own degree of agency.

Particularly useful for writing this was Morgana Regina Santa Cruz Javier’s Master’s thesis on the archaeology of childhood and gender in the case of the children of Llullaillaco in which she also outlines directions in which future research can go.

The Future of the Children of Llullaillaco

After a quick excavation at the top of the volcano, the 3 mummies were carefully transported to the Museum of High-Altitude Archaeology where they have lived ever since. The three are preserved through a complex technical system of cryopreservation designed by a group of Argentine engineers under the direction of Mario Bernaski. This unique system replicates the environment in which the children were found, and the capsules allow for 360 degrees viewing of the children.

The museum prioritises preservation above all else. The mummies are displayed in their cryogenic capsules and only one is displayed at a time, rotated through as to ensure preservation takes precedence over public display.

I have been to the museum twice now and would probably say it is my favourite museum that I have ever been too. The rotations mean I have only seen two of the children, the maiden and the boy, both incredible to see with my own eyes.

As I stood in the Museum of High-Altitude Archaeology, looking at the Maiden seated in her glass capsule, I felt something that is difficult to put into words. A connection—not just to the past, but to a world shaped by beliefs entirely different from my own. It is easy to look at the capacocha ritual and see only the tragedy of it. To impose modern emotions onto an ancient practice. But the truth is, these sacrifices were not carried out with cruelty or malice. They were part of a deeply rooted worldview in which death was not an end, but a transformation.

The capacocha ritual was an act of devotion, a bridge between the mortal and divine realms. As Garcilaso de la Vega wrote:

“These sacrifices were not done out of cruelty, but as a great honour, for the children chosen were of noble blood, and their families took pride in knowing they would join the gods.”

To the Inca, these children did not simply die; they became messengers, intermediaries, sacred beings whose presence would shape the fate of their people.

That does not mean we should ignore the fear and sorrow they must have felt. The Maiden’s lips, flecked with coca from her final moments, the Boy’s bound arms, the Lightning Girl’s preserved expression—all hint at the human reality beneath the ritual. But focusing only on the horror of their final moments diminishes the meaning of their selection. It reduces them to victims rather than central figures in one of the most profound religious ceremonies of the Inca world.

It is tempting to look at these mummies and frame them as evidence of a brutal past, but in doing so, we overlook the fact that their own people saw them as divine. Their story is not just about death—it is about belief, honour, and the way human societies grapple with mortality.

For me, the Children of Llullaillaco are a reminder that the past is not something we can fully possess. We can study it, interpret it, and tell its stories—but we must always do so with respect and humility. The greatest injustice we can do to them is to turn them into a spectacle, a shock value headline, a ghostly curiosity behind glass. Instead, they should be remembered as they were: offerings to the gods, chosen to bridge the gap between the Inca and the divine, their presence a testament to a world that once was.

References

Primary Sources & Academic References

Betanzos, J. de. (1551/1996). Suma y narración de los incas (M. R. de Huerta, Ed.). Historia 16. (Original work published 1551).

Blom, D. (2005). Embodying Borders: Human Body Modification and Diversity in Tiwanaku Society. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

Cieza de León, P. de. (1553/1998). The discovery and conquest of Peru (A. Hamilton, Trans.). Duke University Press. (Original work published 1553).

Gil García, F. (2002). Donde los muertos no mueren. Culto a los antepasados y reproducción social en el mundo andino. Una discusión orientada a los manejos del tiempo y el espacio. Boletín del Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 31(1), 37-66.

Javier, M. R. S. C. (2017). Arqueología de la Infancia y de Género: El caso de Los Niños de Llullaillaco (Argentina). [Master’s thesis]. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid.

Reinhard, J., & Ceruti, M. (2010). Inca rituals and sacred mountains: A study of the world's highest archaeological sites. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Verano, J. W. (2016). Bioarchaeology of high-altitude Inca sacrifice: Ritual, environment, and cultural context. In B. J. Baker & T. H. T. Elgvin (Eds.), Sacrifice and the body: Perspectives from bioarchaeology (pp. 193–211). Smithsonian Institution Press.

Vitry, C. (2007). Los caminos rituales del volcán Llullaillaco, Argentina. Boletín de Arqueología PUCP, 11, 315-336.