What do a medieval mercenary from Castile and the King of Gondor have in common?

Quite a lot, it turns out. Aragorn is a fictional hero shaped by historical echoes, and that’s fine- Fiction invites us to dream. The problem begins when we try to reverse the process, reshaping real historical figures to fit our ideals of heroism. Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known as El Cid, was a real person. But the ambiguity of his life and the gaps in our sources have made him a blank canvas, easily adapted by those seeking a hero for their own narrative.

Who was El Cid?

The real man behind the legend of El Cid was Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, an 11th-century knight who served both Christian and Muslim rulers. Above all, he served his own interests. Few primary sources survive that document his life in detail. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some scholars even questioned whether he had existed at all, likening him to mythical figures such as King Arthur. Today, however, his historical existence is clear. He appears in Latin charters, the Historia Roderici, and in the writings of Islamic chroniclers.

Rodrigo was born in Vivar, near Burgos, in 1043. He first gained recognition as a military commander in the service of King Sancho II of Castile, earning the title Campeador, meaning “champion” or “battle master.” He lived during a politically complex period, before the Reconquista had solidified into a religious crusade. Rodrigo fought both Muslim taifas and Christian rivals in the fragmented kingdoms of the north.

After Sancho was assassinated in 1072, likely at the instigation of his brother and rival Alfonso VI, Rodrigo entered the new king’s service. However, his position soon became precarious. Alfonso sent him to Seville to collect tribute from its Muslim ruler, a routine payment made in exchange for military protection. At the same time, Seville's rival, the taifa of Granada, was also under Alfonso’s protection. When conflict broke out between the two, Rodrigo led troops in support of Seville, which meant attacking another of Alfonso’s client states. In the battle, he clashed with Count García Ordóñez, a trusted ally of the king. This created a serious political embarrassment and likely led to Rodrigo’s exile in 1081.

During exile, he entered the service of the taifa of Zaragoza. It was here that he earned the title El Cid, a Castilian rendering of the Arabic al-Sayyid, meaning “my lord.” He gained the respect of both Muslim allies and enemies.

In the early 1090s, Alfonso, facing renewed threats from the Almoravids, invited Rodrigo back into royal service. Although he nominally accepted, Rodrigo operated with considerable independence. By this point, he had become a kind of autonomous warlord, a term that continues to spark debate among historians. In 1094, he captured the city of Valencia and ruled it as his personal domain until his death from natural causes in 1099.

The Legacy of El Cid

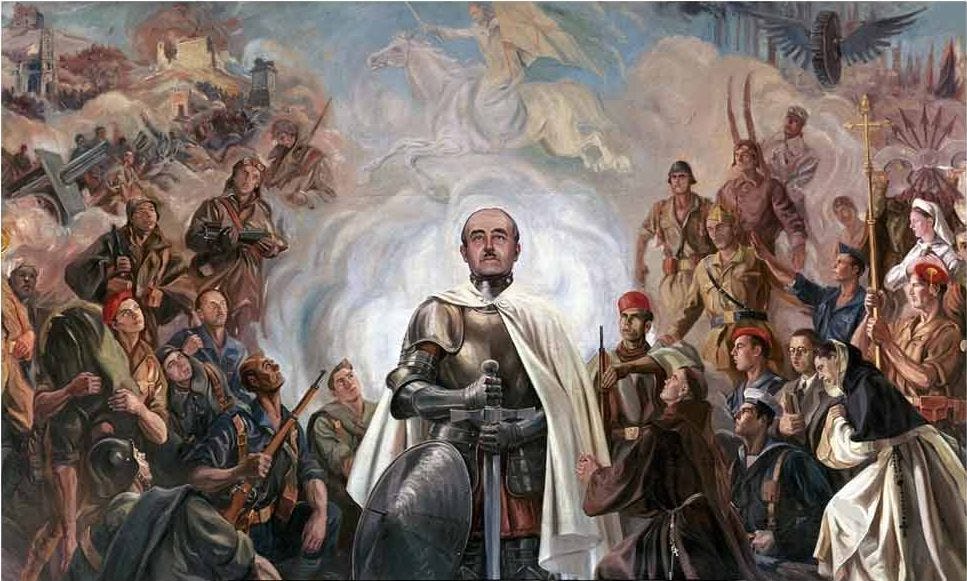

During the fascist regime in Spain under dictator Francisco Franco, El Cid was adopted as a symbol of Spanish nationalism and Catholic supremacy. Streets, parks, and schools were named in his honour, and he was celebrated as the embodiment of the righteous Christian knight who fought to reclaim Spain from Muslim rule. This image aligned perfectly with Franco's desire to portray himself as the saviour of a unified, Catholic nation.

One of the most influential figures in shaping this image of El Cid was the historian and philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal. Decades before Franco’s rise, Pidal had portrayed Rodrigo Díaz as a unifying figure and a symbol of Spanish identity in his 1929 work La España del Cid. He framed El Cid as loyal, honourable, and Catholic, and as a noble warrior who embodied the virtues the regime would later claim as its own. Though Pidal’s work was not intended as propaganda, it provided the intellectual foundation that made El Cid such a convenient hero for Franco’s Spain.

But within this carefully constructed myth lies a deep irony. When Franco launched his military uprising in 1936, it began with the support of Hitler and Mussolini, who provided the aircraft to transport troops from the Army of Africa across the Strait of Gibraltar. This army included not only Spanish legionnaires but also thousands of Moroccan soldiers, many of whom were Muslim. In trying to cast himself as a modern El Cid, Franco led a campaign that, like Rodrigo’s own, was shaped by religious and political complexity. The very myth he embraced was built upon a history far more ambiguous than the propaganda allowed.

The man himself was reduced to a simplified figure, stripped of nuance and repackaged as a champion of Spanish imperialism and Catholic dominance. Even today, some still promote this image of El Cid as the Christian warrior hero of the Reconquista.

On the other end of the spectrum, modern reinterpretations have created a different kind of myth. In recent years, El Cid has been presented as a symbol of coexistence and religious tolerance. His diverse alliances and shifting loyalties are used to cast him as a mediator between cultures, a bridge between Christian and Muslim Spain. Some portray him as a visionary navigating the multi-faith reality of medieval Iberia with flexible identity and intercultural awareness.

This, too, is a distortion. El Cid was not a champion of pluralism. He was, above all, a pragmatic and ambitious figure. His alliances were forged for strategic advantage, not for utopian ideals. He was a man who served himself, motivated more by power and opportunity than by principle. In both cases, we are dealing not with Rodrigo Díaz the man, but with El Cid the idea.

El Cid on Film: A Legend for All Sides

John F. Kennedy, a liberal democrat who publicly championed human rights and democratic values, was ideologically opposed to Franco’s dictatorship. Despite this, both men admired the 1961 film El Cid, starring Charlton Heston as Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar. The film presented a sweeping, romanticised version of the Cid legend, filled with grand battles, tragic love, and noble sacrifice.

In this version, Rodrigo is portrayed as a larger-than-life Christian hero, defending Spain from the Moors with unwavering devotion and honour. It is not the historical man, but the idealised myth.

Kennedy reportedly screened the film multiple times at the White House. It appealed to his Cold War worldview, in which the West stood as a bastion of moral clarity in the face of existential threats. The character of El Cid, as depicted in the film, represented duty, sacrifice, and righteous leadership—values Kennedy liked to associate with his own presidency.

For Franco, the film was an opportunity to export his preferred version of history. He permitted filming in Spain, supplied locations, and even offered extras from the Spanish army. It was the perfect tool to reinforce the narrative of El Cid as a Catholic nationalist icon, perfectly aligned with the values of the regime.

So while El Cid the film entertained audiences around the world, including JFK, it also became a powerful instrument of ideological storytelling. In the hands of Hollywood, El Cid became a hero of Western values. In the hands of Franco, he became a sanitised emblem of authoritarian virtue.

The King of Gondor

And if we’re talking about cinematic warrior-saints crafted from history, it’s only fair we turn to Middle-earth’s most noble exile: Aragorn.

Aragorn is not based on one historical or fictional figure, but rather a blend of many European traditions. He carries echoes of King Arthur, Beowulf, and Alfred the Great. In Alfred, we see one of the central arcs of Aragorn’s story: a king in exile who endures hardship with patience and humility, preparing for the moment he is called to lead.

This idea also appears in the story of El Cid. Rodrigo accepts exile from a king suspected of murdering his former liege, endures years of marginalisation, and eventually returns in triumph as the ruler of Valencia.

Aragorn is composed, selfless, and unwavering in his sense of duty. He moves through the world with quiet strength, guided by noble lineage and a destiny that is clear and righteous. The idea of El Cid, as shaped by political myth and romantic legend, shares the surface qualities of the heroic exile: loyal, valiant, and divinely favoured. Both are presented as men who rise from the margins to restore order and honour.

In both stories, violence is not just necessary but noble. Aragorn’s sword, like El Cid’s, is a symbol of justice, often wielded without ambiguity. Their battles are glorious, their enemies conveniently evil or foreign, their victories righteous. Death is romanticised, sacrifice is exalted, and bloodshed becomes a pathway to legitimacy.

I’ve been watching The Lord of the Rings every couple of years for almost as long as I can remember. My mum is a huge fan of the films. She had the extended editions, the companion books, and all the behind-the-scenes features. When I was young, she explained why the films weren’t rated 18 or even 15 in the UK (or R in the US). The reason, she said, was simple: the violence was mostly against orcs.

Orcs are fictional, recently born, nameless creatures. They are stripped of personality and agency, created purely to be killed. Aragorn’s sword cuts through them without moral ambiguity because their deaths carry no emotional weight. The audience is never asked to consider their inner world, or whether they might have one.

You can probably see where the problem lies when we start taking the same approach to someone like El Cid.

But where Aragorn’s legend is purpose-built to represent moral clarity and ideal kingship, the image of El Cid has been bent in different directions depending on who is holding the pen. He has been a fascist icon and a multicultural mediator, a holy crusader and a tolerant warrior. These versions say more about the people who created them than about the man himself.

Aragorn was made to be a symbol. El Cid was made into one.

Conclusions

We are free to project our ideals onto characters like Aragorn because they were built to carry them. Fiction is a space for imagination, for exploring who we want to be. But history asks something different of us. It asks us to accept complexity, contradiction, and the uncomfortable parts of our past.

The danger comes when we try to turn historical figures into vessels for modern ideals. El Cid has been used to justify conquest, nationalism, tolerance, multiculturalism, and empire, often all at once. Each version reveals more about the storyteller than about Rodrigo himself. When we do this, we strip history of its rough edges and smooth it into a narrative that feels good but teaches us little.

It is tempting to reach into the past and find heroes who validate our present values. But real people, especially those who lived in fractured, violent times like El Cid, were not moral symbols. They were calculating, courageous, self-interested, and often contradictory. To truly understand them, we have to let go of what we want them to be and reckon with who they actually were.

That doesn’t mean we can’t have heroes. Aragorn shows us what leadership might look like if it were unclouded by compromise. He exists in the space of what should be. But El Cid lived in the world as it was, and it’s in that messiness that real historical understanding begins.

El Cid may have died in 1099, but the battle over what he represents is still being fought.

But the Soviets were pure evil, there’s no question about that