A visit to the British Cemetery in Buenos Aires

Three Anglo-Argentines that helped shape Argentina

Recoleta Cemetery is one of Buenos Aires’ most visited tourist attractions. Famous for its grand mausoleums that tower over shadowed walkways, this beautifully eerie part of the city is the resting place of Argentina’s most famous figures.

Five miles west in the quiet neighbourhood of Chacarita is another, much less visited, cemetery. Here you won’t find grand mausoleums but rather a scattering of simple tombstones, marked with simple religious indicators: the star of David, the Christian cross or perhaps a freemason symbol or two. A simple chapel is surrounded by trees and well-maintained lawns but elsewhere in the cemetery nature has taken over. Ivy clings to every fence and structure, weaving its way up the water towers that stand in the centre of the graveyard. The greenery is a remarkable contrast from the neo-gothic stone tombs in Recoleta, and the songs of birds make you feel as if you are in the secret garden, not in the middle of a city of 15 million people.

Every so often the silence is broken by the gentle ringing of the level crossing outside the cemetery as a train passes by, one of the few lasting marks the British have left on the city. Another of those marks being the cemetery itself, the Cementerio Británico de Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires British Cemetery). The names of these people do not line the streets of Buenos Aires, or have parks and plazas named after them, but many of those buried here helped shape and influence the nation in which they are buried.

Thomas Bridges: (1842 – 1898)

What had inspired me to visit here in the first place was to see the grave of Thomas Bridges who featured heavily in one of my presentations. Thomas was born in Bristol, England. Allegedly found abandoned on a bridge, giving him his surname, Thomas would travel to the Falkland Islands at 13 years old with his adoptive father, in the hopes of setting up a mission in Tierra del Fuego. After his father left, Thomas founded a settlement at Ushuaia and made a home for the indigenous Yaghan people.

The Yaghan had been dismissed by the likes of Charles Darwin who had previously met them and had said of these people that they “scarcely deserve to be called articulate”. And yet, Thomas, who spent much of his life with these people, had compiled a dictionary by the end of his life, translating their language into English. Noting its intricacies, such as having five different words for snow and different words for canoe depending on the context of its positioning such as on a beach or in the water.

When the Argentines came to Tierra del Fuego in 1884 to claim the territory, Thomas had no complaints in lowering the colony’s flag and raising the Argentine colours. He thanked the Argentines for allowing him to operate on their land and asked only for a small piece of land of his own where he could live out the rest of his life as his health worsened.

During his time at his new estancia (ranch), Harberton, Thomas would offer shelter to the Selk’nam people of Tierra del Fuego as a systematic extermination of the indigenous people took place. His son, Lucas Bridges (buried alongside his father), would go on to live much of his life in Tierra del Fuego where he was born and would become the first of European decent to be made a blood brother of the Selk’nam and witness their council.

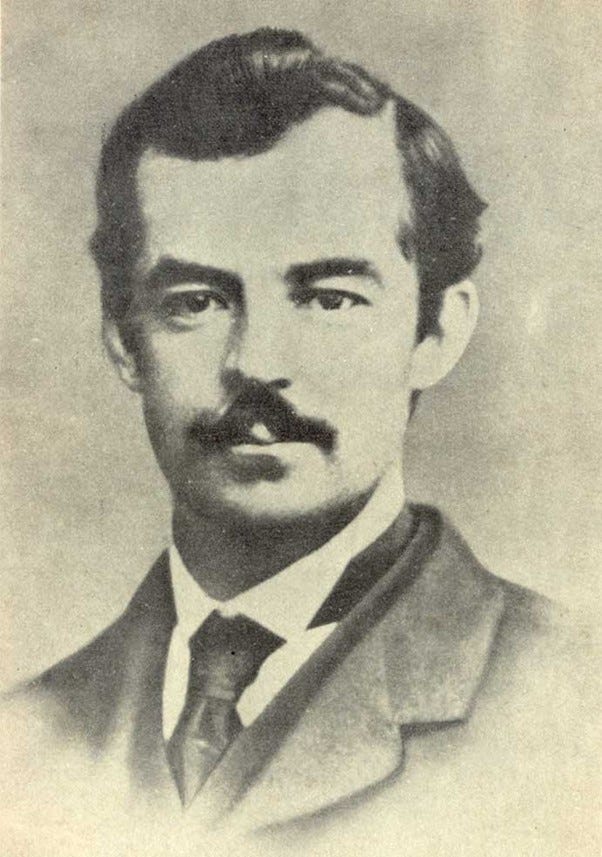

Alexander Watson Hutton: (1853 – 1936)

Alexander was born in Glasgow, Scotland but became known as the “Father of Argentine Football” after claiming to have brought association football to the country. He was the headmaster and founder of the Buenos Aires English Highschool, and his team, made up of school alumni, dominated the Argentine Association Football League, where Hutton served as president of for several years.

Although you cannot think of Argentina without thinking of football, Alexander’s achievements went beyond the title of the “Father of Argentine Football”. I do not want to paint Hutton as a leading feminist. The school he founded, whilst co-ed, still focused primarily on conventional values, preparing girls to become mothers and housewives, and boys for office work. He did however invite Cecilia Grierson, the granddaughter of Scottish colonists in Buenos Aires and first woman in Argentina to receive a medical degree, to speak on “The Education of Women” while Watson Hutton was president of the English Literary Society in 1894. He also sponsored a debate on the motion “Social and political rights should not depend on sex.” And even employed Grierson for a time to work at the school and encouraged girls to be involved with sports, building the cities first women’s tennis court at the school.

Watson Hutton also embraced bilingualism, making space in the curriculum for classes to be taught in Spanish which opened up the school to children from different backgrounds. Hutton clung to many British imperial values – commitment, willpower, integrity, the games ethos and military heroism, but these values coexisted alongside his strong patriotism towards the Argentine Republic.

On his retirement Hutton claimed he “had done everything in his power to mould [his pupils] both physically and mentally to take their places as leading citizens of this great Republic.”

Gordon Stretton: (1887 – 1983)

Gorden Stretton is accredited as introducing Jazz in Latin America (something close to my heart as I enjoy attending jazz shows in Buenos Aires). Gordon’s mother was Irish, his father Jamaican, and the young Stretton spent the early years of his life in poverty in the slums of Liverpool.

At 5 years old, he snuck into a theatre in Liverpool and began to sing from the crowd. Like some kind of Disney tale, he was invited up on stage to join the choir. From that point on his music career began to take off and at age 9 he was in a singing group, touring music halls in the UK. In 1914 he signed up for the army but served only 2 years after sustaining an injury. While recovering in hospital, he met his wife Molly Smith, who was working as a nurse at the time.

By 1923, Stretton’s career had taken him to South America, and he never looked back, never returning to Europe for the rest of his life. He was brought to Buenos Aires by a local businessman to perform and began a 3-month tour of Argentina in 1928. By the mid-1930s, Stretton had his own Radio show and led live performances as part of his 14-piece band, being invited to perform all over Buenos Aires and even special performances in Brazil.

Stretton didn’t forget of home and when the second world war broke out, he raised funds for the British air force and International Red Cross through performances. 886 Argentines of British decent would lose their lives fighting in Europe during the World Wars, a place they were connected to despite many of them never having been there. A monument in the cemetery stands in their honour.

Gordon had a long career as a musician as well as co-founding the Argentinian performing rights society, starting and running a dance academy, and co-authoring a requiem in a radio broadcast across Argentina on the first anniversary of Eva Perón's death.

His last performance was at the age of 92 in 1980 at the famous Café Tortoni in Buenos Aires, three years before his death.

A country of Immigration

In the 1850s, as the nation of Argentina was in its infancy, the governor of Buenos Aires, Valentín Alsina expressed his wish that someday Argentina could “delete from the pages of public law the disagreeable word “foreigner””. Argentina is a nation that was founded upon the idea of attracting European immigrants to settle their huge territory. The consequences of this were not always positive, but it has shaped Argentina into the country that it is today. With Welsh colonies in Chubut, Bavarian towns in Patagonia, and Italian sounding Spanish spoken in Buenos Aires, the country is a melting pot of cultures.

But Argentina’s rise in a strong sense of nationalism and the events of the war in 1982 have obscured from history some of those British ties. The 'British Square' that stands in front of Recoleta Train Station, which itself was mostly built in and then shipped over from Liverpool, has been renamed to the 'Argentine Air Force Square,' and the tower that was built by the British community that stands in the square’s centre as a gift to the Argentines has been renamed from the 'Tower of the English' to the 'Monument Tower'.

It would be a shame for these people’s stories to go forgotten. For myself, having chosen to make Argentina my home, I can find relatability in the lives of some of these people who shared a deep love for this country, while being unable to detach themselves from the customs and values they were brought up with back home. And at a time of much debate over the effects of ‘multiculturalism’, Argentina provides an example where we Brits have been immigrants ourselves, coming to a new land with the promise of opportunity, developing a deep love for our adoptive countries, and working hard to better them.